- Welcome / History

- Sites 11-22

- 12. Zuncker House 2312 N Kedzie

- 13. Kreuter House 2302 N Kedzie

- 14. Gainer House 2228 N Kedzie

- 15. Lost Houses of Lyndale

- 16. Beth-El / Boys & Girls Club

- 17. Madson House 3080 Palmer

- 18. Erickson House 3071 Palmer

- 19. Lost Schwinn Mansion

- 20. Corydon House 2048 Humboldt

- 21. Symonds House 2040 Humboldt

- 22.Painted Ladies-1820 Humboldt

- Flipbook & PDF

As you enjoy this guide, please consider donating to Logan Square Preservation to support the work we do.

The Logan Square Boulevards District

Celebrating 15 Years as a Chicago Landmark

Logan Square is anchored by the Logan Square Boulevards District, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985 and became a Chicago Landmark on November 1, 2005. Encompassing 2.5 miles of the larger Chicago boulevard system, this district includes Logan and Kedzie Boulevards, and sections of Humboldt Boulevard, as well as Logan Square proper (the Square) and Palmer Square.

The neighborhood features a distinctive and remarkably intact group of single-family houses, small flat buildings, larger apartment buildings, and small-scale commercial, institutional, and other buildings built between 1880 and 1930 that reflect fine detailing and craftsmanship seen in such building elements as cornices, porches, windows, and doors, the overall collection of stylistic examples, ranging from excellent to modest, illustrating (among many architectural styles) Second Empire, Queen Anne, Richardsonian Romanesque, Classical Revival, Prairie, and American Four-Square influences, and for the high quality of materials including brick, stone, wood and metal.”

The first owners on the boulevards were well-to-do, but not so wealthy that they could replicate the mansions they envied in the Gold Coast, or along Prairie and South Michigan Avenues. Still, when they hired architects, they expected them to incorporate many of the same elements into their projects. Referred to as “stylistic eclecticism,” many homes and flats feature an assemblage of corner towers and turrets, crenellated parapets, dormers, pitched gable roofs, and projecting porches — with classical details and ornaments such as bay windows, columns, balustrades, brackets, and pilasters. The architects didn’t seek any consistency of style; it seemed that symmetry was outlawed and flats were made to look like single-family homes.

Architects then transitioned and translated the forms and exuberance of Logan Square’s greystones into brick. To do so, they used contrasting zones of colored brick and brick texturing. Stone was used to accent for window surrounds, cornices, and other decorations. Symmetrical designs began to appear with the use of Prairie, Classical, and Tudor Revival styles.

The designers of the houses on the boulevards are too numerous to mention; more than 75 can be identified, and many more would be involved with the surrounding blocks. A few stand out, having designed more than a dozen structures. Charles F. Sorensen, a Danish immigrant, designed residences in timber, stone, and brick, as well as churches and stores, between 1890 and 1915. Brothers Fred and John Ahlschlager, who grew up on a farm in Mokena, Ill., designed stores, apartments, and some of the biggest houses on Logan Boulevard. The partnership of Worthmann & Steinbach (John Steinbach, in particular) was responsible for designs of residences, flats, at least one major commercial structure, and several major churches.

Why is Chicago Landmark Status Important?

The primary purpose of Chicago Landmark status is to maintain the beauty and character of a neighborhood by preserving its historic buildings and preventing overdevelopment. A National Register designation does not prevent demolition; the City of Chicago designation is the only designation that protects against demolition or significant alteration of the façades of the buildings that are visible from the public right of way. Owners can alter the sides and rear of their buildings, as well as the interiors. Non-contributing buildings in a landmark district can be demolished, but the Commission on Chicago Landmarks regulates what replaces them in accordance with its design standards. Several hundred buildings are considered to be contributing buildings in the Logan Square historic district, ensuring that much of its original look will remain for future generations.

Brief History of Logan Square

The Kimbell Homestead

Originally prairie and marsh, with woodland along the Chicago River, the area now known as Logan Square saw its first white settlers arrive in the 1830s. In 1836, the year before Chicago was incorporated as a city, New Yorker Martin Nelson Kimbell (for whom Kimball Avenue was named, with the change from Kimbell to Kimball in the 1920s) and his wife Sarah Smalley-Kimbell (for whom Smalley Court was named) claimed 160 acres in the area now bounded by Diversey, Kimball, Fullerton and Hamlin avenues and set up a homestead near what had been a Native American trail prior to 1830.

According to John Stehman’s Souvenir Program of the Logan Square Festival & Circus, July 20-23, 1932: “When planked in 1849 and 1850, this thoroughfare become known as Northwest Plank Road and was used by farmers to bring their goods to market in Chicago. Unfortunately, with time the planks warped and decayed, slipped out of place, or broke as heavy loads passed over them. Some floated away in spring floods, and some were carried off by people who needed firewood.” The Northwest Plank Road became Milwaukee Avenue Plank Road. Today’s Milwaukee Avenue was not paved until 1911.

According to John Stehman’s Souvenir Program of the Logan Square Festival & Circus, July 20-23, 1932: “When planked in 1849 and 1850, this thoroughfare become known as Northwest Plank Road and was used by farmers to bring their goods to market in Chicago. Unfortunately, with time the planks warped and decayed, slipped out of place, or broke as heavy loads passed over them. Some floated away in spring floods, and some were carried off by people who needed firewood.” The Northwest Plank Road became Milwaukee Avenue Plank Road. Today’s Milwaukee Avenue was not paved until 1911.In 1850, the area that includes Logan Square was incorporated as Jefferson Township after President Thomas Jefferson. Initially a relatively unpopulated, rural community, it stretched from Devon Avenue on the north, Harlem Avenue on the west, Western Avenue on the east, and North Avenue on the south. Stehman goes on to say “Mud roads, large open plains, dotted with a few frame homes, an occasional all in one store, a ‘good old country school,’ and a church, were the main constituents of early Logan Square.”

Growth was spurred by the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, as affordable wood-frame structures could be built since Jefferson Township lay outside of the city’s restrictive post-fire building code. With relatively inexpensive housing available, this area was a favorite of immigrants and working-class citizens. Early residents were primarily English, German, or Scandinavian. Norwegian-Americans established several large churches, the most famous of which is today known as the Minnekirken at 2614 N. Kedzie Boulevard (Tour Site 2).

Outgrowing Planks

In 1892, a streetcar line was extended along Milwaukee Avenue, and in 1895, an elevated rail line was built parallel to Milwaukee, terminating just south of the Square, spurring the growth of Logan Square.

Again, according to Stehman: “Many new subdivisions were opened and the old ones showed new life. Lots sold readily and many homes were built. The population increased rapidly. Schools and churches multiplied and farms and market gardens vanished. The Square became a business center. Logan Square Ball Park was established and soon became famous. Retail business of all kinds flourished. Substantial business blocks were erected along the [Milwaukee] Avenue and the population increased very rapidly. Up to 1915, there were no large apartment buildings. Single family homes and two- and three-story flats were the rule.”

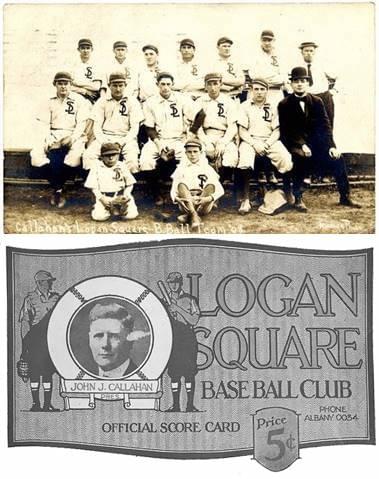

Comiskey's Rival

In 1906 Jim “Nixey” Callahan, a former White Sox pitcher who was alienated from franchise owner Charles Comiskey, started a semipro baseball club. Callahan bought and fixed up an old amateur ball field in Logan Square at Milwaukee and Diversey. Signing the best talent available, regardless of their status with other clubs, the Logan Squares fielded a championship team. At the end of its first season, the Logan Squares defeated both the White Sox and the Cubs, both of whom had just competed in the 1906 World Series.

The Boulevard Plan

By 1869, the system of interconnected parks and boulevards originally proposed in 1849 was authorized by the Illinois state legislature. Although intended to be a unified system, three separate park commissions were established on the north, west, and south sides of the city. The West Park Commission’s section was designed by William Le Baron Jenney and subsequently revised by landscape architect Jens Jensen.

At the time they were designed, many of the West Park Commission’s boulevards were within Jefferson Township. Although platted, the Logan Square boulevards remained largely unimproved during the 1870s,1880s, and early 1890s due to a series of national recessions and panics and the West Park Commission’s own financial challenges.

As public transportation was being extended to Logan Square in the 1890s, the Commission began to improve the boulevards with pavement, sidewalks, streetlamps, and trees. Large single-family homes were built along the boulevards, followed by two- and three-flats and small apartment buildings in the 1900s. Churches, other institutional buildings, and commercial buildings were also built at this time.

Larger apartment buildings and additional institutions followed in the 1910s and 1920s. During 1918, the Illinois Centennial Monument (Tour Site 1) was built in the center of the Square to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Illinois statehood on October 14, 1918.

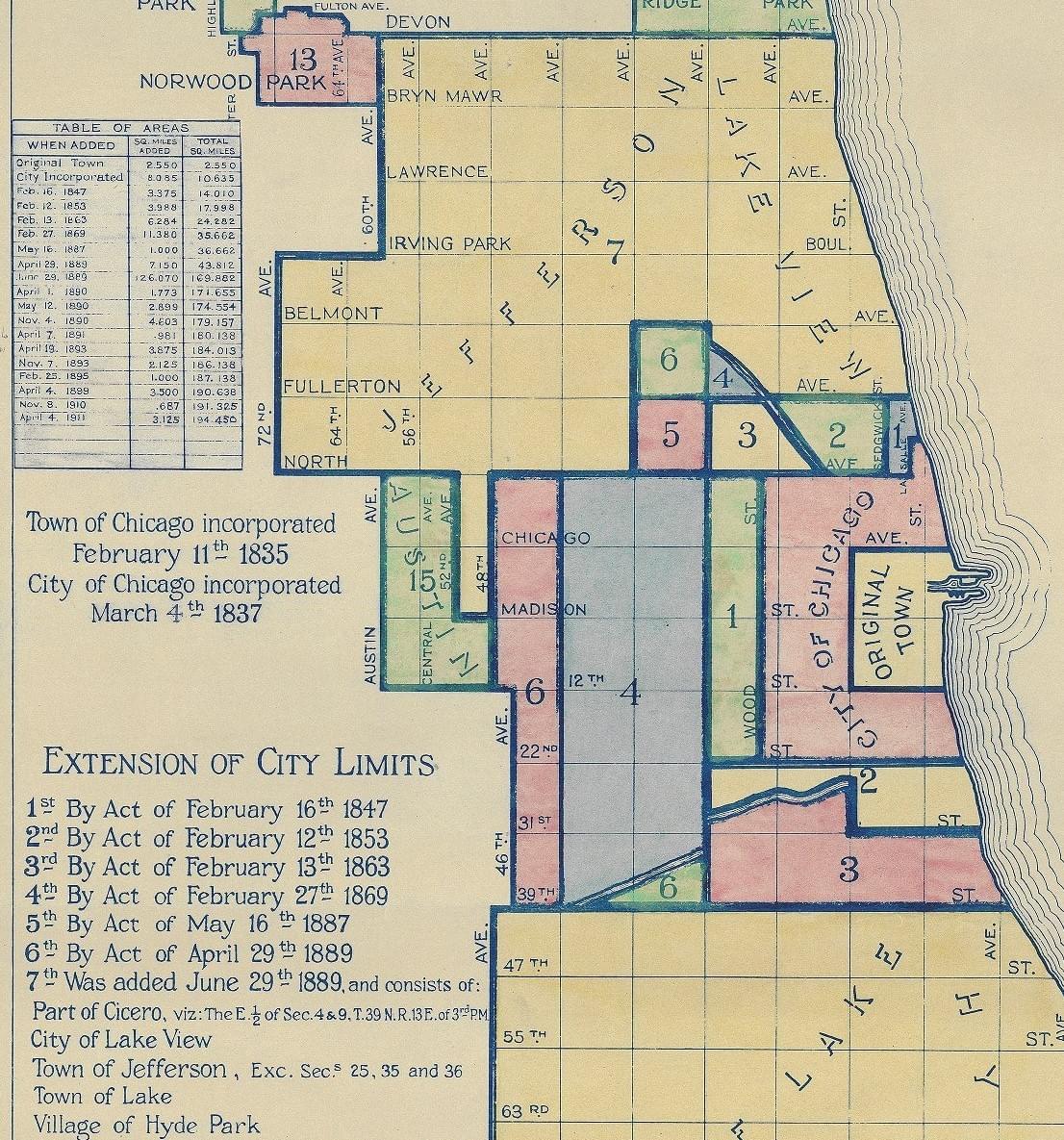

Becoming a City

Excerpt from Annexation Map of Chicago, 1911

By 1889, poor infrastructure and limited municipal services led Jefferson Township and other large municipalities to agree to be annexed into the City of Chicago, creating the largest city in the U.S. at that time. Parts of Logan Square had been annexed by the City of Chicago in increments a few years earlier, but the move brought the remainder of what is now Logan Square into the city. The area was named Logan Square after Gen. John Alexander Logan (1826-1886), a Civil War general, Illinois State senator, and a U.S. Senator.

Post-World War I

Following the end of WWI in 1918, Logan Square boomed and by 1920 it had a population of 108,685. English, Germans, and Scandinavians were slowly replaced by Poles, Russians, and Jews. In 1925, developers claimed the last sizable tract of open land, the Logan Square Ball Park. Most of the streetscapes of the Logan Square Boulevard Historic District were complete by the 1930s and a peak population of 114,174 was reached that year. But the Great Depression led to the departure of many residents. Houses, particularly smaller, wood-frame cottages, and factories along industrial corridors fell into disrepair and started a reversal of Logan Square’s fortunes.

1950s to Today

Logan Square owes much of its early growth to its access to transportation routes, from the Northwest Plank Road to the “L” line. But just as quickly, access to a new transportation route would lead to a further decline. By the late 1950s, construction of the Kennedy Expressway led to the departure of affected residents. In the 1960s, the CTA rebuilt its Northwest Side transit line (now the Blue Line), extending it to Jefferson Park (and eventually to O’Hare International Airport in the 1980s). Construction of the Blue Line further disrupted commercial life in central Logan Square. The original Logan Square “L” terminal was demolished, and the line was placed underground with a new station. Entrances are marked by the small-scale International Style metal pavilions located on the north side of the Square.

As Logan Square’s original immigrant groups moved to outlying areas, the 1960s brought an influx of Hispanic residents from Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Mexico seeking affordable housing like the immigrant groups before them. This allowed Logan Square to avoid the massive population drop experienced by other neighborhoods during this time. By 1990, Hispanics made up almost two-thirds of Logan Square’s population. The influx of entrepreneurial Hispanic residents who established businesses and restaurants is said to have saved Milwaukee Avenue, and many Hispanic-owned businesses continue to thrive today.

Starting in the early 1980s and accelerating into the 1990s, access to public transportation and high-quality housing stock once again brought significant attention to Logan Square as artists and young urban professionals moved in, purchased, and rehabbed old buildings along and off the boulevards. If anything, this revitalization has accelerated since the Logan Square Boulevard District was designated a Chicago Landmark in 2005, serving as evidence of the value placed on beauty, architecture, history, and community by the residents of Logan Square.

Logan Square Preservation

Share your experience of Pillars & Porticos

Copyright © 2020 Logan Square Preservation. All Rights Reserved.